“I thought everyone would be going down the elimination path and follow the success of Asia.”

Reporters Online Exclusive

While populations across Europe and North America are preparing for a harsh winter and the most austere Christmas in ages, their fellows in a country far away are in an entirely different situation. Early in the pandemic, New Zealand decided to go for elimination of the coronavirus. At just 100 cases and zero deaths, the experts ascertained they were – just like us – not ready for containment. But instead of waiting for the hospitals to get overwhelmed first, the government rapidly proclaimed a lock-down, in the meantime built up the capacity for testing and tracing and instated strict border control measures.

Despite some small and one ‘large’ outbreak of 179 cases, they have managed to keep the number close to zero, with just over 2000 cases and 25 deaths in total. As a result, people are enjoying all freedoms they were used to before COVID-19. But hey, New Zealand is an island, and it has a very low population density, so it would be impossible to copy anything they’re doing, right?

Or is it something else that keeps us from drawing lessons? I decided to ask the architect of the New Zealand approach, public health professor Michael Baker of Otago University in Wellington. A softly toned, patient man, with grey hair and a fancy pair of glasses, logs in on Zoom at 11 pm, New Zealand time for a conversation that would last over an hour. ‘No problem, I would be working late anyway.’

First of all, what’s the current situation like in New Zealand and how is the virus impacting daily life?

Well the virus per se is not having impact, because it isn’t here. What we’re seeing now is the consequences of the response. One is to keep the border shut and some things that are only mildly inconvenient, like limited mask requirements for flights. Furthermore it is mild inconveniences like encouraging people to scan a QR code when they enter a place. Only about 10 percent of the population are really using this app. We’ve been slow to adopt digital tools to support contact tracing, but our manual contact tracing system has worked well. So we have no virus impact except for people with long COVID. We have the economic effects caused by the pandemic in general and two sectors are directly affected: international tourism and international students.

To which extent is the international tourism replaced by national tourism?

It actually was about half that much. The other counterfactual is that even if we would have opened our borders for tourists, they wouldn’t have come anyway. It’s is really died down because obviously the cruise ships in particular are not going to come any time soon. Iceland had this experience, which was written up in Nature recently. They decided that tourism was too important. But not many tourists came and they did get outbreaks, so they paid quite a big cost. The GDP data for the whole world has just come out in the last few days and it’s showing that in general, countries that have gone down the elimination path have done much better than those trying to suppress the virus.

You mean the number one position in the Bloomberg rating of places to be during the current stage of the pandemic?

This is the true IMF projection for the whole year. It’s interesting, the U.K. and a lot of countries in Europe have taken quite a big drop in GDP this year.

And you’re doing pretty well, right?

Yes. There’s always been the right wing groups that said it’s a choice between public health and the economy and chosing the economy will save more lives. But that is not correct.

Well, within the European narrative it could be a trade-off. But once you flip to elimination the two seem to come together. One other thing I was wondering about the current situation in NZ: are the quarantines for incoming travelers being replaced by rapid testing yet?

The standard is two weeks of managed quarantine. Aircrew who are going backwards and forwards have less quarantine and more testing, and they have tight protocols of what they do when they’re overseas. But now some of us are saying we need to move to a more risk based system. So far the one size fits all model has worked well for New Zealand. Since we opened up a little bit, we’ve had a few border failures, but mostly just single cases and family members. So obviously, we’re hoping we can sustain that for a few months until the vaccines become available.

And is there free travel with some countries?

That idea is gradually developing. Technically, we could have done that months ago with most of Australia, but not all of Australia because they had varying levels. And it’s the same with the Pacific islands. Some of them never had a case. New Zealand’s has been a bit wary about introducing the virus to those islands. So I think it has to happen because among other things, when the first batches of vaccine arrive, we would do the border workers first. And at that point, it’s going to become quite easy to open up with Australia and the Pacific Islands. Yeah, technically, we could probably end up with Taiwan, maybe even mainland China.

I can imagine that with additional testing at the borders, that might fit into a risk based approach.

The level of disease in Australia is the same as New Zealand now, with just a small outbreak in South Australia at the moment which seems under control. So really, it’s mainly about policies and procedures. But I would say a lot of people are reasonably comfortable now. Most people feel they just want to have a high level of security and they can put off the overseas trip for another year.

To which extent is this approach still depending on the collaboration of the population? Behavior seems less important than within the European approach?

That’s exactly right. Now people in New Zealand are doing everything they would normally do. They’re going to big stadium sports events, they’re going to nightclubs, all the high risk things you don’t do if you’ve got circulating virus. That’s the benefit of elimination.

The Guardian published a piece about such a small outbreak and it felt like a parallel universe: so much is being done when there are just one or two cases. How do you get the people so alert when there’s just a couple of cases? People here would think: ‘well, it’s two people who will probably be asymptomatic.’ Is it just the different narrative?

I think people have totally got the idea that the ‘go early, go hard model’ is the way to go. One case is a major event and it’s headline news. This is one of those remarkable changes in thinking, you are right it feels like a parallel universe compared to your reality. We’re so focused on the idea that we must eliminate every last case. I guess it’s like putting your finger in the hole of the dike when it’s a little hole, before it turns into a giant waterfall — CONTINUE BELOW

Reward this article

If you value this article, please show your appreciation with a small donation. This way you help keep journalism independent

Let’s go back to the early phase. You were also on the ‘flatten the curve’influenza plan, just like the European and North American countries, right? Could you tell me how that flipped after you read the WHO-China joint mission report?

Basically the message I got from that report is the Chinese in Wuhan have done what people thought was impossible to respiratory pandemics once you no longer have a couple of hundreds cases, but thousands: they eliminated it. A lot of us were looking at the footage that was coming through and saying: well, you could only do this in a very harsh regime. Then we looked at our information sources like the WHO, CDC, ECDC, Public Health England, the places where we normally get our advice from. But they weren’t really saying anything: it was more or less just carry on with the influenza model. I found that quite worrying because we weren’t getting any guidance from there. Then we looked at what Asia was doing, which was very much about containment. They never used the term elimination. They don’t even have a term for what they were doing, they just did what they thought was necessary.

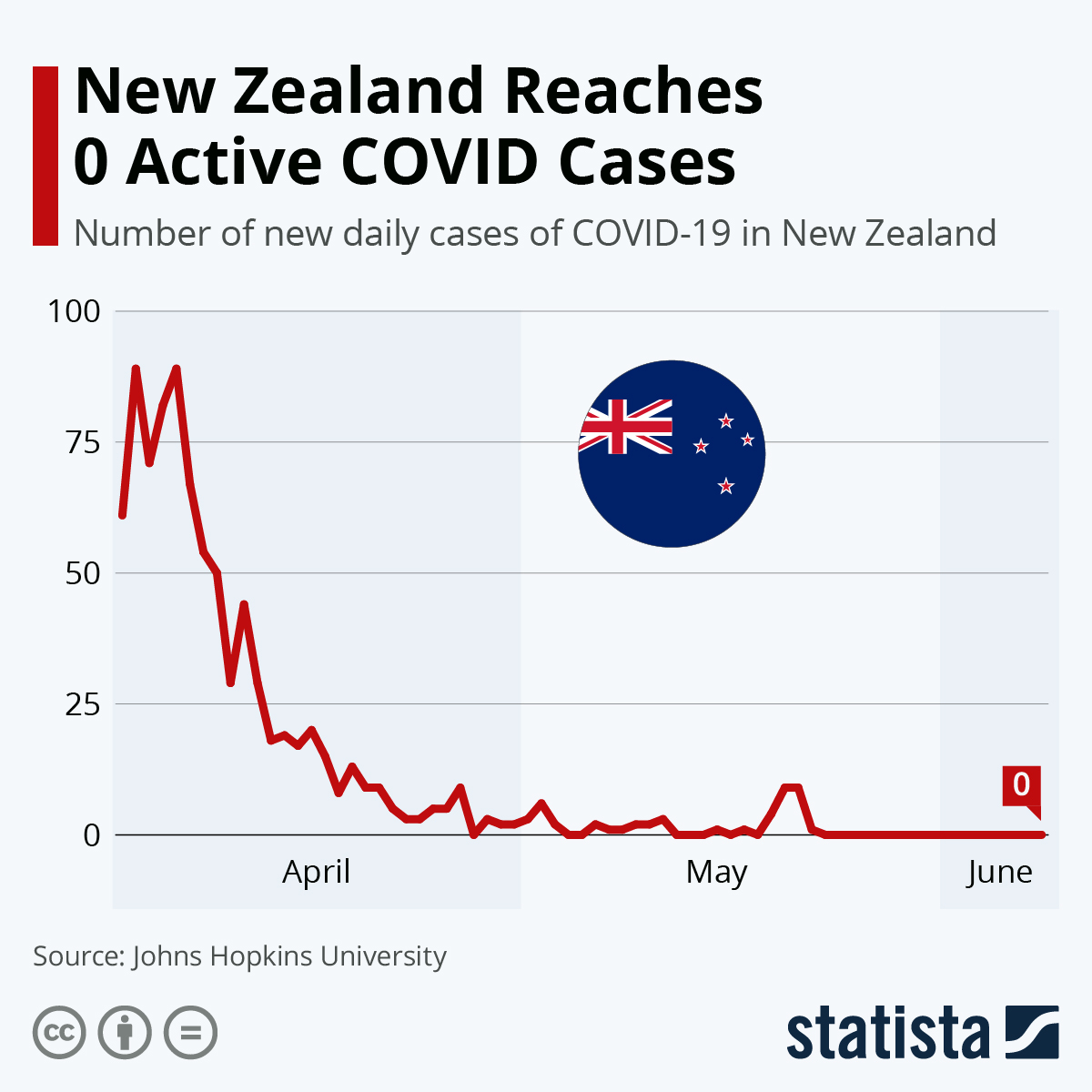

You will find more infographics at Statista

You will find more infographics at Statista

Some of the Dutch modelers interpreted the mission report as: ’there must have been some herd immunity, because otherwise the transmission would not have gone down that quickly. Very differently.

Well, if the modelers get hold of the problem, they treat it like influenza. And with influenza you get a nice clean pandemic wave that would come through very quickly. Most people get sick and get over it. In New Zealand it would all be over in about six weeks and probably it would have been in most countries in Europe. But this virus never behaved like that.

It does have some similarities to influenza, right? This virus can be spread presymptomatically and possibly asymptomatically, which resembles influenza more closely than SARS. So it is somewhere in between SARS and influenza.

One of the distinguishing factors aboutthese coronaviruses is that they seem to behave much more like clusters of outbreaks rather than more evenly like influenza. Only 20 percent of the introductions sparked additional transmission in New Zealand and that seems to be still the case around the globe, right?

It seems so, yes. I was wondering why you took a more ‘Asian’ approach than we did. Could it be cultural, or at least geographical?

We are still actually quite Anglophile, following CDC, ECDC and the WHO. But WHO said initially: keep your borders open and use lockdown as a last resort and don’t use mass masking. The countries who did the opposite from that performed much better.

The taboo on closing borders, was that evidence based? Is seems ideological.

Yeah. I did quite a bit of work on the international health regulations that came to be in 2005. The primary aim of those is to let countries share their emerging problems with WHO to minimize the risk of a public health emergency of international concern. But one of its other aims is not interfere with the movement of people and trade unnecessarily. In the past, countries have used the threat of infectious diseases as a tool to excessively limit trade by other countries. So WHO was trying to find that balance. But in doing that, it errs too much on the side of not limiting trade and travel. And the other thing is, in the past, the consensus has been that you could never stop an influenza pandemic by closing borders. I think this prevailing idea did more harm than good.

You used the lock-down to scale up your testing and tracing capacity, which wasn’t ready like in some Asian countries. How did you manage?

One of the things that astounded me was the speed with which the public service in New Zealand shut the whole country down in just a few days. According to the Oxford government response tracker we had the tightest lockdown in the world, for five weeks followed by two weeks at a lower level of strictness. The R went down to 0.35 and basically that was the end of the virus. It just had nowhere to go.

It seems to have worked so well because it was early, right? Countries like Italy had a very strict lockdown as well but by that time the virus was already inside many family homes.

Absolutely. The number of chains of transmission to extinguish was not vast. And you could see it as a bit of a sledgehammer to crack a nut. That’s actually one of the main criticisms: we might have been able to do it with a less severe lock-down.

The Dutch ‘intelligence lock-down’ did pretty well, although we didn’t maintain it long enough to to get that testing and tracing capacity built.

That is the fundamental difference. I can understand why there’s resistance to lock-downs now across Europe and North America, because people don’t see where’s they’re taking them. You need to use the time to build your capacity so that you can stamp out any remaining hotspots. If it’s still in the community, it’s going to come back – this is its very nature. And I have to say it is quite staggering that a country like China managed to do it, with one point four billion people and long, complex border. They’ve had a lot of transmission at a certain point, and they’ve succeeded. It’s an amazing achievement. I mean, the only place that’s done better is Taiwan, which never needed a lock-down.

It all seems to boil down to basic public health measures. How has your public health background helped you?

As a clinical doctor I always loved the systems approach. So I did five years of training in public health and epidemiology and I’ve carried on in that area. Everything is reminding me over and over again that governments can save you or kill you, depending on how functional they are. I’d much rather see they put more effort into saving people. And I think also the areas of equity and sustainability are still the two most critical things. The dichotomy has been around for 30 years: you either control diseases or you eliminate them. And I remember looking at this and thinking, why are people not talking about elimination? That’s what China has been doing. I thought everyone around the world would be going down the elimination path and follow the success of Asia. They didn’t and I found it quite shocking.

Some of the European countries, like Germany, did try to achieve containment following the first lockdown, but seem to have failed. What do you think were the decisive factors?

Well, the countries that have succeeded are not necessarily wealthy countries. Vietnam, Thailand, Mongolia, Cambodia, Laos and other countries that have done pretty well, like Hong Kong and Singapore. South Korea and even Japan, said at different times: we really want to eliminate the transmission from the community. They’ve had setbacks and some have decided it was too difficult and moved to intense suppression. But they generally have done well in terms of mortality and economy.

In Europe, it seems that the main difference is not so much the contact tracing and going after the virus, but border control, national or within larger zones.

I think across Europe, countries and regions have proven to be pretty good at shutting the borders during this crisis. Just as Australia did between states. Fundamentally it was still the conceptual issue of what they were trying to achieve and I still don’t know why. The World Health Organization adopted almost an ideological stance against elimination. There’s a bunch of experts who still have exactly the same views that I’m talking about and articulating these very vigorously, I’ve done probably a couple of hundred interviews with overseas media, and they’ve all been focused on this. There is the independent Sage group in the UK that has put out an elimination proposal. So I think the view is there, but for some reason it hasn’t gained currency with government agencies and the World Health Organization.

One of the other things that people see as part of the issue is that for, say, France, they have all these big cities with neighbourhoods that the government has little control of. Do you think that makes sense? That you would need either a low population density or an authoritarian regime to succeed?

That’s possible. Though, the countries that succeeded have included liberal democracies like Australia, New Zealand and Taiwan is quite a liberal democracy as well. Yes, we are islands but certainly a place like Ireland and the UK have no biological barrier to doing this.

Do you see other reasons why most countries never tried to go for elimination?

Well, if COVID-19 had been considerably more lethal or had obviously more serious consequences, it might have been an immediate decision. The flu pandemic of 2009 was no more lethal than seasonal flu. Maybe that left some residual resistance to taking dramatic measures against this virus, which is far less lethal than SARS. So I think the major view that has been prevailing initially, was it’s something we can manage and live with.

And then they felt stuck in their chosen path?

People will be probably analyzing this decision making for a long time. For me, it seemed like a major error of risk assessment not to consider elimination. Quite early on, we knew this virus had the infection fatality rate of a half to one percent. Obviously, hugely influenced by the age structure of the population. Many countries should, based on their population structure, have realized they were not in a good position.

During the BMJ webinar you recently participated in, an Indian colleague said: ‘We will just have to go for natural sterilizing immunity because we cannot contain it and we wouldn’t even get the vaccines there.’ Can you understand that?

Oh yes. Many low and middle income countries have got so many other health issues they’re trying to manage. And the opportunity cost is much higher and the ability to succeed with elimination is very low.

I also talked to Chikwe Ihekweazu, the director of the Nigerian CDC, who was part of that joint mission. He said: ‘well, this is not going to work in Nigeria. There is way to much freedom and way too little state control.’

That I can imagine. It’s interesting, indeed.

In Europe, freedom seems to be an issue as well. There is a lot of resistance to quarantines and people are questioning the reliability of the PCR test these quarantines are based on. In Portugal, a judge ruled the quarantine of four German tourists of which one tested positive illegal.

I hadn’t heard that. You don’t have to know much about testing to develop a healthy skepticism for tests. They are just one tool. These tests will never be 100 percent sensitive or specific and they’ve got limitations.

But it depends on your goal, right? It is public health here, not clinical medicine. Once you get those individual approaches dominating the discussion, you cannot do public health.

Actually, lawyers are often the worst in these situations. You never want them to be running the public health system because they are steeped in an individualistic approach. A lot of what you want will in some ways compromise individual rights to achieve protection at population level, for the greater good, for the greatest number. Lawyers don’t generally help at all with managing pandemics.

Has the debate been been fierce in in New Zealand about individual rights? I can imagine it is not as bad as here because the citizens have more freedom, currently.

I think the public want powers to be used well. They don’t like to see rule breakers and people who pose a risk to others. They generally want quite a regulated response. Obviously you have to always think about human rights and privacy and ethics and values should be at the core of what we’re doing. So all of those trade-offs need to be very carefully worked through. We have privacy commissioners to scrutinize everything very carefully.

That’s one of the issues people are raising: we don’t want to sacrifice our privacy. How did you translate what you saw in the report about China to your own, liberal context?

I think people accept the trade-off. The law on dealing with infectious diseases does give the state very strong powers. A lot of this isn’t about this disease, about things like tuberculosis or people who pose a risk to society for other reasons. I think the law accepts that sometimes it is necessary to intervene against people’s individual rights to actually serve their population. That wasn’t a hard sell in New Zealand.

You co-authored a paper on potential lessons from the pandemic responses of New Zealand and Taiwan. What are the most important ones?

The main one was having a dedicated, well resourced public health agency tasked with scrutinizing threats on the horizon. Policy oriented agencies like Ministries of Health, don’t look at this sort of thing. The other ones were more timely managing the borders and a greater approach to mask use. The fourth was greater use of digital technologies for things such as contact tracing.

I can imagine you would need to be prepared and have a very good technical team that can rapidly decide which approach to take.

The most prepared countries, according to the Global Health Security Index, did not necessarily do well. We were pretty well down the list. But that might have kept us free to take a different approach and not roll out the influenza plan.

You might also have had less famous modelers to build on.

Well, there is huge soul searching going on in the UK about why they got it so wrong. One of the reasons they say that during their initial talks, too many modelers were involved and their mindset dominated.

Combined with exceptionalism.

Yes. Well, I love the term the editor of The Lancet used to describe the Western World: complacent exceptionalism. Just thinking it won’t be as bad as it was in Asia. Relying on their superior technology and everything else. But it didn’t protect them.

Do you have one last message for those who are skeptical of elimination?

The history of eliminating diseases is very strong. Normally you need a vaccine to do it. But we had two huge revolutions this year: first there is the absolute exceptionalism of the vaccine development and ultimately, vaccines will be the way out of this. But while you wait for the vaccine I think you have to eliminate these diseases when they appear using these methods we now know work. The biggest lesson for me is that we have to be ready with an elimination approach if this happens again and apply it very swiftly and not question whether it’s a good idea. I mean, this is not esoteric epidemiology. This is the most basic level of framework. It’s been around for decades.

What do you expect for the next months?

I think with vaccines coming, that’s obviously going to be a dominant topic. But actually, with vaccines available there still remains a choice: are you going for elimination or are you just going to protect the vulnerable? Given these vaccines are effective, elimination may well be the preferred approach. So that you won’t need to worry about the virus any more. It still strikes me that even that debate isn’t taking place at the moment.

Reward this article

If you value this article, please show your appreciation with a small donation. This way you help keep journalism independent